- Home

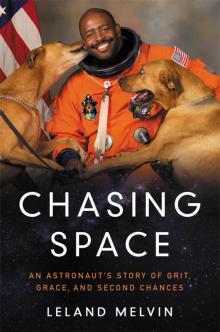

- Leland Melvin

Chasing Space Page 4

Chasing Space Read online

Page 4

I didn’t understand it then, but I had been given an opportunity that would alter the course of my life. The fact that others believed enough in me to give me a second chance—even after I failed before—inspired me to persevere against the odds and to never give up. It wouldn’t be the last time I would get a second chance.

3

Second Chances

I stared into a plastic cup that had just been handed to me. Inside it was a swirling mass of snuff spit, Tabasco sauce, and a bunch of other dubious substances. It was my first night at the University of Richmond and the whole team was on hand as a huge three-hundred-pound offensive tackle acted as master of ceremonies and our chief tormentor. Twirling his massive arm above our heads, he snapped the tip of a leather whip. “Drink,” he commanded.

Welcome to college football, I whispered to myself.

Before long I found myself tied up to defensive back Taylor Lackey, whom I’d known for only a few hours. Together we were thrown blindfolded into the bed of Billy Cole’s pickup truck. Taylor and I lay back-to-back and practically buck naked, as the truck bounced along for what seemed like hours. It was only a day into training camp and Taylor would soon distinguish himself as an outstanding safety, a fierce hitter from rural Georgia who could knock the crap out of whatever stood in his way. But on that particular night we were both helpless as we lay there in our jockstraps, sweating in the heat.

When the truck finally stopped, the players yanked us onto the train tracks and left us as they sped away. I remember hearing a train, its horn blaring louder and louder as we lay there. It seemed like we would be crushed at any second. The train never came. We found out later that the sound of an oncoming train was actually an air horn attached to Billy’s truck. The challenge now was to get back to the Robins Center on campus without getting arrested for indecent exposure. First we had to get out of our blindfolds without the use of our hands. We didn’t have a clue where we were and the dark, starless sky made it difficult to navigate. My stomach was still churning from the initiation phlegm cocktail I had downed.

“Where the hell are we?” Taylor yelled. As we walked, I saw the familiar lights of the library. We hadn’t gone as far as it seemed—we were on the edge of campus about a half mile from the Robins Center. Billy must have driven us around in circles. We sprinted from bush to bush, hoping not to be spotted in our jockstraps.

We finally made it back to our rooms. At practice that morning, everyone suited up and stood on the field as if nothing had happened. The relentless July sun beat down as Coach Dal Shealy laid out his strategy for reversing the team’s losing streak. I couldn’t hear any of it. My head was pounding too loudly.

On my second night in the dorm we were led down the hall to the big communal bathroom where the veteran players were shaving the heads of the freshman. Could be worse, I remember thinking. I didn’t have a lot of hair anyway. But Don Miller, a linebacker, didn’t take it so lightly and refused to open his door. “Go to hell,” he snapped. “I’m not going to do it!” The upperclassmen kept banging, telling him to come out, telling him he’d regret it if he didn’t, and soon dozens of us crowded into the hallway eager to see what would happen next.

Don didn’t open the door. Instead he slid open the window of his second-floor room and jumped. Miraculously he landed on his feet and sprinted across the courtyard. But a few hours later, he came creeping back into the building, where he was ambushed and whisked into the bathroom. The boys were waiting, and in short order Don’s head was shaved down to the skin.

In some ways, those hazing rituals helped prepare us for the rigors of Coach Shealy’s training. He was someone you didn’t want to disappoint. He had played football at Carson-Newman College, a Baptist school in Tennessee, and then joined the Marines, where he played for the legendary Quantico Marines. Coach Shealy retired two years after I had graduated, and he went on to become president of the Fellowship of Christian Athletes, an interdenominational Christian sports ministry. Coach never cut us any slack. He was relentless when it came to training, pushing us to both physical and mental exhaustion.

To all of us on the team, Coach Shealy was the model of decorum, a Southern gentleman from South Carolina who considered coaching his God-given mission. He forbade swearing and routinely led the team in prayers. He didn’t fare that well stopping his players from roughing each other up and drinking to excess after the games, especially when we lost. He sought players who had character and enough grit to become part of a team.

“My philosophy was to coach the way I like to be coached,” he later told me. He described the men who had guided him as “people coaches” who wanted “to teach you to be a man, to teach you to live life and be the person you should be.”

Somehow he got the best out of us.

Our Losing Season

They say that in the South some traditions refuse to die. At the University of Richmond, football was one of them. The 185-year-old school had fielded an NCAA football team for more than a century before I got there. But the year I arrived, the program was in serious trouble.

For the past six seasons, the Spiders had lost more games than they had won. Every year there was talk about killing the program, and the year before I got there the critics were louder than ever. But legend has it some powerful alumni stepped in and convinced the school the program was worth saving. They cut a deal to pay for renovations to City Stadium, the 20,000-seat facility three miles from campus where the Spiders had played since 1929. The football program was saved, at least for the time being, though having to play home games off-campus made it hard to keep students interested, especially when the team was still losing. To top it all off, the football program had just been dropped down from Division 1-A to 1-AA, an NCAA decision that devastated the coaches. That was the scene I stepped into when I moved into Jeter Hall that fall.

With the start of classes I found myself thrown into a punishing schedule of training and practices while I tried to keep up with a full load of math and science courses. It was a good night when I managed to get five hours of sleep. My mom and dad came to nearly every game, even if it meant driving a full day or more from our home in Virginia to upstate New York or even Rhode Island. My mother worried constantly that I might get hurt. I later found out she prayed I would get a minor injury so I would be taken out of the game and avoid a worse one.

During my freshman year we lost every single game and ended the season 0–10, but the worst part was that we were demonized around campus. Complete strangers snarled at me or would shake their heads in disgust. Loser. You suck. Being an athlete had always been part of my identity, but that season caused a lot of us to question what we were doing there.

The University of Richmond was a small school with about 2,100 students and, it seemed to me, a lot of money and an aura of entitlement. When you’re on an athletic scholarship and your team is losing, school administrators, fellow students, and even professors make you feel like you’ve let them down personally, like you weren’t doing your job, or like they paid for an expensive product that didn’t operate as advertised. Of course, there’s that underlying belief that certain athletes couldn’t possibly deserve to be there on their academic record alone.

A few days into the school year, I sat in a meeting with my freshman advisor, Dr. J. Ellis Bell, and about twenty other students. Dr. Bell asked for a show of hands from those who were exempt from taking certain classes because of their AP test scores. “Like Leland here,” he says. “He’s exempt from taking calculus.” I could detect a palpable sense of surprise throughout the room. What, him? The black football player? I could practically hear their thoughts. Some of them even raised their eyebrows.

I was relieved when the season ended and I was able to go home for Christmas break. It had been a long and hard introduction to college—particularly college football. I had never been on a losing team with an 0–10 record. I looked forward to returning home to a family that was proud of me no matter how many games we lost.

Hot chocolate, a warm fire, and the scent of pine in our house on Hilltop Drive provided familiar, much-needed comforts. Exhausted from a season of game travel, training, study hall, classes, and final exams, I was relieved to finally be all done. I just wondered about my inorganic chemistry grade.

I thought I’d done well, and I liked chemistry since I was a kid. I’d had a B in the course all semester, so I wasn’t too worried. To hear the professor, Dr. William Myers, tell the story later, I wasn’t his strongest chemistry student that year, but I was perhaps his most determined. I didn’t get discouraged at not having the answer right off or making a mistake in a hypothesis. He saw I had the potential to become a scientist and, as a supremely gifted teacher, he looked forward to helping me achieve that.

When an envelope came from the University of Richmond I knew it contained my grades. However, there was no letter grade for my chemistry class. Instead, there was an X—rather than the B I had expected. I assumed Dr. Myers had simply not finished grading finals before the break, though that was not like him. Like most serious scientists, he was meticulous, efficient, and always graded our tests within a few days of our taking them. I would also come to learn that he was a superb writer, as competent with words as he was in a lab. Still, I wasn’t worried as the knotted pine popped in the fireplace and all seemed right in Lynchburg.

Honor Council

After a few weeks at home, I started looking forward to getting back to Richmond. I was tired of listening to friends constantly ask how our football team had done. They all knew we had not won a game; they wanted to rub it in about being a loser. Big-time college football player didn’t win a game. I drove back to Richmond from Lynchburg ready for a new start, beginning with off-season football training. I was also eager to find out my chemistry grade. I went straight to my dorm and dropped off my bags. I remember getting a call on the hall phone to come to the student commons to talk to Stephen Kneeley, the student head of the Richmond College Honor Council. I figured the council had decided to invite me to join as a new member of the council. Wow, that’s pretty cool, I thought to myself. And I’m only a freshman. Sure, I was busy with football and school, but I thought this would be a good chance to get noticed for something besides the gridiron.

I entered the room and exchanged greetings with Steve. The next words I heard from him sounded like an unintelligible foreign language. It was as if he were speaking in slow motion and then time stopped momentarily as I tried to grasp what he had just said. He told me I had been accused of cheating in Dr. Myers’s inorganic chemistry class. Thoughts of becoming an Honor Council member vanished as I tried to figure out what was going on. The council members looked concerned, but I knew they believed I was guilty.

The charges had been brought against me by a senior named Tom, who lived across the hall from me. He was a business major struggling in what was known as “football chemistry,” the basic level class for nonscience majors. Tom needed a final exam grade of B to graduate and asked me to tutor him, even though he probably hated the idea that a football player was possibly making an A in a much more challenging chemistry course. Tom was also a member of the Honor Council. He alleged that he had heard me discussing the chemistry exam I was scheduled to take with another student. The other student happened to be his girlfriend. She was a freshman and had taken the exam earlier that day. She had walked into the room where we were celebrating Tom’s getting the B he needed to graduate.

The truth was I did hear the girlfriend describe the test, and I didn’t bother to tell her to stop. I simply didn’t care, nor did I need the help since I had performed well throughout the semester. She had taken a different test anyway, it turned out. But, Tom decided to turn both of us in, and we had to stand trial.

The Honor Council was composed of a dozen or so white students, mostly male, seemingly selected for their proximity to wealth and privilege. At the time, the number of minority students at the University of Richmond amounted to 0.01 percent of the student body. No one on the Honor Council looked a thing like me, the small-town football player. The fact that the Spiders had lost every game that season didn’t help my case much, and instead probably bolstered the arguments of those who wanted the school to drop the football program altogether. They’re not only losing—they’re cheaters! The council was overseen that year by Dr. Richard Mateer, a university dean and by coincidence a chemistry professor.

The trial took all of fifteen minutes. I did not receive any help with my defense; no one from the school’s administration ever talked to me or explained my rights. I was alone facing a panel of students who knew nothing about me but held enormous power over my future. The panel found me guilty of cheating and suspended me from the university for a semester.

After I left the trial I walked to my dorm and sat on the steps as the tears streamed down my face. The worst part was that I had to call my dad and tell him I had been suspended from school. I figured I’d lose my scholarship.

That day could easily have been my last at the University of Richmond. But as I sat with my head buried in my hands, my roommate, Dan Fittz, came out and said I had a call on the pay phone. Dr. Myers wanted to see me. Dreading what he would say, I dragged myself to his office. I had disappointed him, and he wanted an explanation. But, when I sat down in his office his demeanor was not what I expected. The Honor Council had recommended to him that he give me a failing grade in his class, but he couldn’t do it. I was not, in his words, an F student, but rather a student who had made a serious mistake.

Dr. Myers knew that my failing that class could have altered the course of my academic career in ways perhaps impossible to reverse. All semester Dr. Myers had been impressed that I had effectively balanced the rigor of his course with my schedule of daily practices and near-constant travel. He decided that, since I had worked that hard, he would fight for me.

Years later when I contacted Dr. Myers to discuss the cheating accusation, he was reluctant to talk about it, regarding it as a deeply personal episode that he’d put behind him. Yet he conceded that he had considered me guilty of the charge. Regardless of whether I used it or not, I had received advance information about the exam. The question for him, he said, had been what to do about it. He felt there was no appropriate sanction, at least not among the harsh sentences that were being proposed. I had made a grave mistake that day by not leaving the room, but he was not going to let that mistake impact the rest of my life.

As part of my punishment for poor judgment I had to take an ethics course and work in Dr. Myers’s chemistry lab until I graduated. “There is something wonderful about seeing the patterns that abound in nature, and there is something more wonderful about helping others see those patterns,” he once told an interviewer when asked about my time in his lab. While showing me those abundant patterns, he turned me into a scientist.

I remember that the following year I took organic chemistry, a notoriously difficult course that typically weeds out weak students. Many take it over the summer so they can focus on just it, since it’s a required prerequisite for medical school. There were two options: Dean Mateer’s or Dr. Stuart Clough’s class. I chose Dr. Stewart Clough since I had a difficult time with Mateer’s Honor Council. Years later Dr. Clough would tell me that he was initially skeptical that I could keep up because of my demands from football. But I proved him wrong. I remember him walking through the classroom dropping graded tests on the desks of each student, facedown. When he got to me, he laid the test on my desk faceup. It had a B+ written across the top, one of the highest grades that day.

“Very good job, Leland,” he said. Years later, he recalled, he had been impressed that a football player had done so well. I looked down at the grade. “I could do better,” I said. The next year I was awarded the department’s Merck Index prize for the Organic Chemistry Student of the Year, and it was Dr. Mateer, the dean overseeing the Honor Council, who presented me the award.

More than thirty years later, I returned to the University of Rich

mond for a Spiders reunion and took a tour of the new athletic facilities, including a meeting room for the football team. The room had been paid for through the generosity of the Kneeley family. Stephen Kneeley had been student head of the Honor Council in 1983 when I faced charges. He had become a peer during the intervening years and had told me about the family’s gift to the school. I was surprised and touched to see a dedication plaque on the wall, and realized my journey at UR had come full circle.

Tragedy and Turnaround

My professor’s decision to overrule the Honor Council’s sanctions did not win me any friends in some corners of the school, but that didn’t bother me. What did was that people might believe I had actually cheated on the test in hopes of getting a better grade. Once again, I felt like I had to prove people were wrong about me. I also faced another challenge: keeping my friends on the team from carrying out revenge on Tom, the senior who had turned me in. My teammates were outraged. I had always been something of an anomaly on the team, a kid from the rural South who loved science. We were a team, a losing one, but still a team. My boys had my back.

Although football season was over, training continued all year. On the first day of practice after the holidays, and on any Monday following a particularly lively weekend, the team would convene in one of the smaller gyms on campus. Strength and conditioning coach Harry Van Arsdale would close all the doors and turn up the heat, to about 105 degrees. Then we did drills until we threw up.

School didn’t get easier when football season wound down. I knew that working in a lab was key to getting into graduate school and obtaining that lucrative job in private industry. My lab job didn’t leave me time for much of anything else.

I spent a lot of time with my professor, and maybe one other student in the lab. Where football gear included shoulder pads, helmets, and mouth guards, our lab equipment consisted of goggles, lab coats, Erlenmeyer flasks, and glove boxes for working with carcinogenic materials. Sports Illustrated published a photo of me in my lab getup during my senior year, holding a beaker of dry ice while mysterious vapors encircled me. Under Dr. Myers’s watchful guidance, I conducted research on amine-haloboranes from the second semester of my freshman year until graduation, looking at the inductive effects of potentially cancer-curing drugs. Working in the lab sometimes required me to miss most of football practice. Over the years, my teammates took to calling me “Larry Lab” because coaches permitted me to show up near the end, looking pristine after everyone else’s uniform bore all the dirty hallmarks of a tough scrimmage. I absorbed the nickname in good spirits while pointing out that I held up my end of the bargain: The coaches allowed it because they knew they could count on me to hold on to the passes thrown to me in closely fought games.

Chasing Space

Chasing Space